The treatment of resale price maintenance (RPM) cases by competition authorities is becoming stricter. The Turkish Competition Authority considers RPM to be an infringement by object and thus does not analyse its effect. The recent Super Bock decision by the CJEU may potentially bring about a change in this approach.

What is Resale Price Maintenance (RPM)?

Resale price maintenance (“RPM”) is a supplier conduct that is considered a “hardcore restriction” under Competition Law. It can be summarised as a supplier, which is the provider of a good or service, interfering with the price at which its resellers will sell. For example, an automobile importer telling the authorised dealers in its distribution network, “Comply with our recommended list prices; those who insist on not complying will have their profit margins cut”, or a packaged food company monitoring the prices on the shelves of supermarkets and saying, “You are selling so low that other supermarkets cannot match you.”

Online marketplaces and RPM

However, in recent years, the most common form has been firms whose dealers sell through online marketplaces “try to stabilise the price in the market” by monitoring the prices on these platforms. The transparency and competitive environment created by online marketplaces in the distribution networks of undertakings, which are primarily providers of consumer products with high brand value, have led to actual prices falling below the prices they set as recommended list prices. In particular, companies representing imported brands in Turkey accused their dealers of damaging their brand image by selling on online marketplaces in violation of the list prices. However, the real issue is that the supplier company has to consider the complaints of the dealers who represent the brand on the street by investing in a physical store and who are probably much more senior in the distribution network. In such a situation, the supplier may be tempted to prevent the distribution network from becoming less profitable by monitoring the prices on online marketplaces and warning and penalising dealers who supply goods to sellers who place these advertisements.

The number of RPM Investigations is increasing

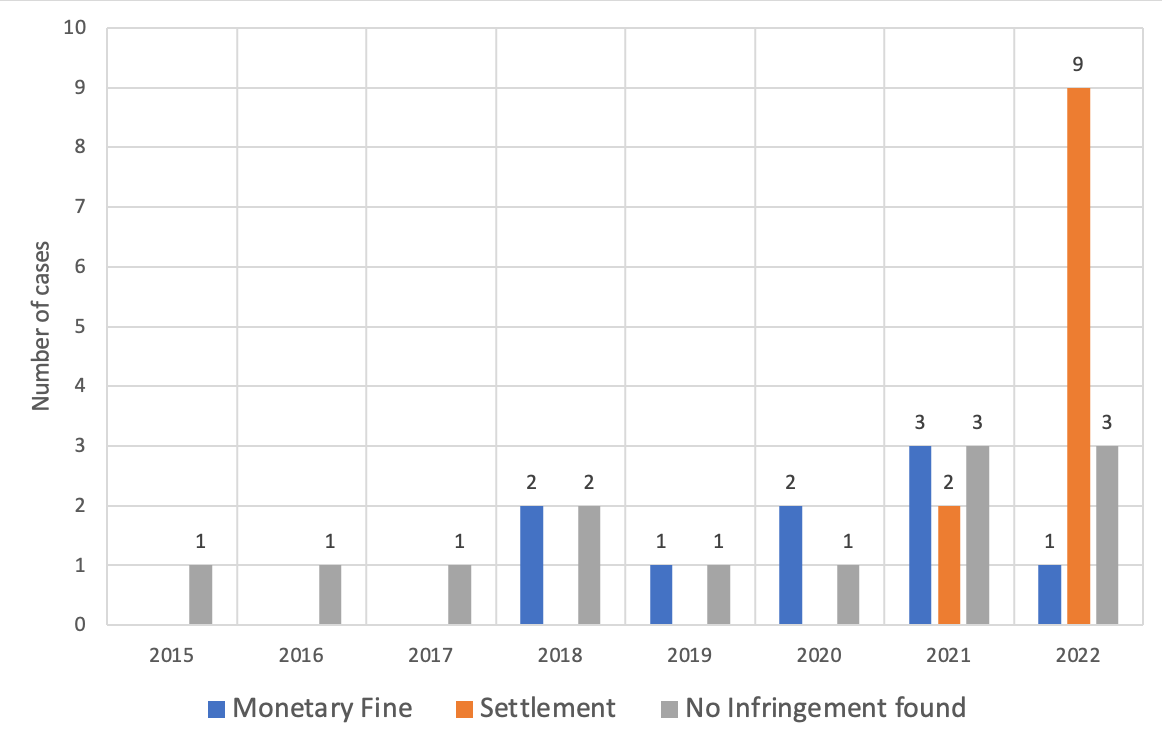

The Turkish Competition Authority (“TCA”) has not remained unresponsive to this movement. While one RPM review was concluded annually between 2015-2017, this number increased to four in 2018, eight in 2021 and 13 last year (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Surge in Turkish RPM cases

When we look at the outcome of these investigations, we see that while no violations were detected in any of the investigations between 2015 and 2017, starting from 2018, undertakings were found to be applying RPM and fined with increasing frequency (Figure 2).

By 2021, three investigations resulted in the determination of a violation and the imposition of administrative fines, while two investigations resulted in the parties reaching a settlement. The settlement procedure, through which undertakings can receive a reduction in the fine by not defending themselves against the allegations against them until the end, was applied in 9 more investigations last year. If the undertakings choose to settle, no investigation report is prepared, and the main text of the TCA’s legal and economic analysis of the undertaking’s behaviour is not produced. Consequently, the undertaking does not have a defence against the allegations and findings against it.

Figure 2: RPM investigation conclusions

Impact Analysis and Factual Verification

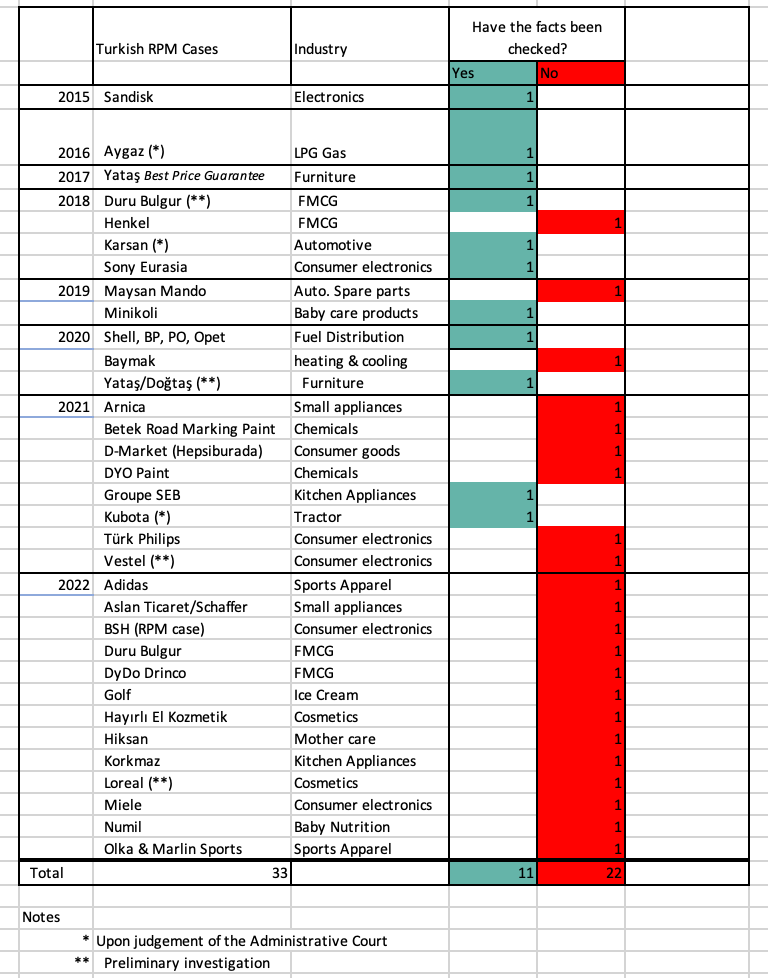

Let us now look at the details of the RPM investigations conducted by the TCA. When we examine the RPM cases conducted between 2015 and 2022, we see that in most of the cases until 2021, the TCA made analyses regarding the impact of the undertaking’s conduct. However, starting in 2021, the TCA no longer endeavours to make a factual verification when examining RPM files (Table 1).

In our review, which is presented in Table 1, we have accepted as “factual verification” any verification as to whether the undertaking actually engaged in the conduct mentioned in the communication evidence obtained in the on-site examination and whether this evidence can constitute evidence of the undertaking general policy. These determinations can take various forms, ranging from individual invoice reviews, list price-invoice price conformity checks, the use of statistical methods on a large number of invoices, or any analysis of the impact of the alleged conduct on the market.

Table 1: Has the TCA carried out factual verification of undertakings’ conduct in RPM investigations?

Is RPM an infringement by object?

It is possible to see hints of the TCA’s failure to make an effort to determine the effect of the conduct in the RPM cases it examined in the Duru Bulgur (2022) decision. As we have seen in other decisions, the decision refers to Anadolu Elektronik (2011) and Toros Gübre (2011). Let us quote the relevant part of the decision verbatim:

“(…) there is no doubt that resale price-fixing practices, the object of which is accepted to restrict competition, fall within the scope of Article 4 of Law No. 4054. Therefore, considering the provision of Article 4, there is no obligation to conduct an impact analysis for the resale price fixing practices in order to reveal the violation.” Accordingly, the practices for resale price maintenance are agreements restricting competition in terms of purpose and are considered infringements under Article 4 of Law No. 4054, even if they do not have a restricting effect on competition. In addition, in the Board Decision dated 19.01.2011 and numbered 11- 04/64-26, it is stated that “Agreements that distort competition create a structural framework in which the parties sacrifice their independent competitive activities in favour of common interests. For this reason, merely being a party to an anti-competitive agreement is prohibited, even if the agreement has not realised its effects.” The Board’s Decision clearly demonstrates that it is not necessary to check whether an agreement, the object of which is to restrict competition, has an effect or not.

TCA, Duru Bulgur (2022), para 128.

In short, the TCA argues that RPM practices are infringements by object within the meaning of Article 4 of the Competition Act, and therefore, it is not necessary to look at the effect.

Does this approach complicate the TCA’s hand in administrative proceedings?

The Court of Justice of the European Union (“CJEU”) in Super Bock (2023) stated

Article 101(1) TFEU must be interpreted as meaning that the finding that a vertical agreement fixing minimum resale prices entails a ‘restriction of competition by object’ may only be made after having determined that that agreement presents a sufficient degree of harm to competition, taking into account the nature of its terms, the objectives that it seeks to attain and all of the factors that characterise the economic and legal context of which it forms part.

CJEU, Super Bock (2023), Conclusion (1).

The TCA’s current approach, shaped in the Anadolu Elektronik decision and has been applied since 2021, is not in line with this principle in the CJEU’s recent Super Bock judgment. Since I will comprehensively analyse the Super Bock decision in a future article, I will only drop this note.

Conclusion

I believe that the Turkish Competition Authority will continue to pursue resale price fixing-type violations, for which it imposed penalties in 12 out of 13 cases concluded last year, because the hawkishness in the RPM policy will be in line with both the international trend and the domestic anti-inflation policies. However, the TCA’s refraining from examining whether there is a parallelism between the communication evidence obtained during on-site examinations and the undertaking’s practice in the market, and more generally its failure to reveal the economic and legal context of the undertaking’s conduct, may lead to its decisions being challenged at the administrative jurisdiction stage.