Competition policy, like everything else in life, can be warmed and cooled by the winds blowing from other countries. Trump’s second term, with winds from the US, Europe and beyond, will profoundly affect Turkish competition policy, especially the public regime for tech giants.

The US election rush is finally over. Donald Trump’s victory continues to shake the world. The Republican Party, which Trump has rebuilt around himself over the past period, has taken the majority in both houses of Congress. He himself will take over the presidency on January 20th. Everyone with a pen in hand and a face on the screen has been speculating about what Trump’s second term will bring, and I thought I would write about how competition policy will be affected.

1. Let’s name the problem: Hipster Antitrust hurts.

Let me give some background information first. As you know, with the Biden era, a team called the New Brandeisians “took office” and tried to erase the traces of the Chicago School, the dominant competition ideology since 1980, in practice. The Chicago School had made it clear that the purpose of competition policy was to maximise consumer benefit and reduce the prices faced by end-users, and argued that even giant mergers should be permitted if necessary to achieve this goal. The New Brandeisers, such as Lina Khan, Tim Wu and Jonathan Kanter, who took the helm of US competition policy in the Biden era, saw the bigness of a company as a problem in itself. The Chicago School’s maxim that the competition authority should decide on measurable parameters such as a decrease in the price of the final product and a reduction of costs due to increased efficiency (for example, whether two companies should merge or not) was overturned during this period.

However, since such an understanding has yet to gain ground in Congress and the US federal judiciary, New Brandeisianism has not yet replaced the Chicago School as the dominant competition doctrine. Academics who also work as corporate counsellors treated it as “Look what the rookies did”, and it is likely that future historians of competition policy will look back on this period as a break.

The demand for a “re-setting” of the tone of competition policy and a not-so-fine-tuning of public policy towards big business, voiced by advisors to the tech giants, found a powerful audience in the US with the outcome of these elections. And yet, there may not be the return to the past that the corporate voices of academia and market elites expect.

2. America First

While it was clear that an approach that had a problem with size first damaged giant US tech companies, it was questionable how politically sustainable it was. Now that the Trump-led “America First” Republicans are in power, a turnaround is expected. Since the announcement of Trump’s victory, all kinds of media have been flooded with comments from stock market analysts claiming that competition policy barriers to technology companies will be lifted and monopolization lawsuits against big technology companies will be dropped. I don’t think so.

Why? First of all, the phrase “prior lawsuits” is incorrect. For example, the first lawsuit against Google was filed during Trump’s first term. Therefore, let’s say the court ruled to break up Google; there is no obstacle for Trump to claim that “Look, we put a monopolistic company in its place in a lawsuit filed during my term. I’m doing everything I can to protect Americans”. There is no indication that Trump has any special affection for digital platforms or giant corporations.

Trump has two approaches that we are sure he will implement in relation to the issue at hand: He will favor US companies over others, and he will do things to favor those who are on his side at the time.

Nevertheless, let’s try to predict where antitrust will go in the coming period based on the two certain data I mentioned above. Let’s also accept as plausible the claim that Trump will seek revenge against all kinds of people, whether real or legal, who took a stand against him during the Biden era. It should not only be seen as revenge: Trump will try to leave no one to work against him, or even to speak out against him, just as he did within the Republican Party. Conclusion: competition policy (antitrust) is exactly what he needs! The power to dismantle, if necessary, digital companies, which have the power to influence not only the economy but also public opinion and popular culture through their digital platforms, in order to ensure that each and every one of them obeys him… I don’t know, it sounds very Trumpian.

What’s more, the tools that Trump has to punish only those who don’t align with him among those doing the same work – in other words, to put it politely , “selective policy ‘ – are abundant in competition policy in general (see the ’case by case” maxim). As fate would have it, in the New Brandeisian toolkit, this quantity is multiplied in proportion.

In terms of policies that would legitimize his favoritism of subservient companies in the eyes of the public, while at the same time not undermining market players’ trust in public authority too much, if tax investigations come first, competition policy comes second.

Apple CEO Tim Cook, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella, and Amazon CEO and Washington Post owner Jeff Bezos, right, tense over what Trump will say next.

Another thing we know about Trump is that he is a system-breaker and anti-establishment. In competition policy, the establishment is the Chicago School and big business dominance. It was Lina Khan who was anti-establishment in this field and demonized by them in all kinds of media. It was the New Brandesians who put the welfare of small businesses (SMEs, will the young reader understand?), workers’ rights and sustainability on the competition policy agenda. What better system disruptors than these!

Let’s take a look at the new team: J.D. Vance, Trump’s deputy, and Matt Gaetz, the member of the House of Representatives whom Trump has announced he will appoint as Attorney General, are the ones who don’t mind being called “Khanservatives”. The vice president and the attorney general, who has the power to prosecute on behalf of the federal government… The news-analysis in the Washington Post, owned by Jeff Bezos, confirms me: The outlook for big tech companies is not bright.

FTC Chairman Khan and Gaetz, whom Biden announced he would appoint as Attorney General, are in the House of Representatives (2023).

On the other hand, Trump’s main focus will be on the US competition with China. To this end, need I say that raising tariffs will not serve to lower the prices faced by consumers? Or that the practices of NVIDIA, the maker of graphics cards, the most important hardware component in the race with China to develop artificial intelligence, will not be heard? Therefore, we should expect neither a coherent nor a Chicago School-style ideological competition policy from Trump.

In conclusion, I don’t think that the anti-big business approach that came to power under Biden will be overthrown in a day like Saddam’s statues. It will lose its coherence, its rhetoric will be hollowed out, but it will not be completely abandoned because it can serve the Trump administration.

3. Then Europe

Let’s look at the situation in Europe. The situation in the European Union is much more complicated than in the United States. The damage caused by the pandemic to society, the fact that it is trying to resist the digitalization of life until the last moment, its dependence on foreign energy sources, the refugees coming from everywhere and the reaction against them, the Russian-Ukrainian war, and many other reasons, Europe is in a state of smoke. Europe’s political elites see no problem in entrusting the helm of foreign policy to the US, but they are very uncomfortable with the fact that domestic politics is being affected by populist and chauvinist waves coming from the same place.

The German government collapsed on the evening of Trump’s victory speech and early elections will be held at the end of February. Far-right movements, already strong across Europe, are in power de facto in Italy and in spirit in France. In Germany they are kicking down the door. And now, the use of the X platform, controlled by someone like Elon Musk, to shape public opinion ahead of the elections… Ouch, it’s overwhelming to write!

EU’s new Competition Commissioner Teresa Ribera

Let’s talk about competition policy. Teresa Ribera, a climate change expert, recently appeared before members of the European Parliament before taking office as competition commissioner, replacing Margheret Vesteger, who also held the title of Vice President of the European Commission. Ribera will wear two hats: Climate change and competition policy. And competition is likely to be of secondary importance to climate change, a particularly pressing issue for European industry.

It remains to be seen whether he will be as strong and as powerful as his successor Vesteger. But I have written before that the Trump administration will not stand by while its own tech giants are beaten up in Europe with the Digital Platforms Act (DMA) and similar regulations. And I wrote once:

None of the platforms already declared as gatekeepers and restricted in their actions are of European origin: the five largest of the six companies are American. So how does this make Americans who say “America First” feel? Republican Senator Ted Cruz accused Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Chairwoman Lina Khan of sending experts to the European Union to help pass “this anti-American legislation”. Senator Cruz is part of the team that supported Donald Trump’s presidential candidacy in January. Let me make a prediction: The DMA will be one of the first targets of a possible US lockdown due to the November elections. Therefore, the DMA’s success will partly depend on its ability to manage the perception of this “anti-American legislation”.

Again, let me continue with my argument: I expect the DMA to continue its life without hurting too much, or, if it is appropriate to say so, without breaking heads.

Because: The famous platforms designated as gatekeepers are the biggest carriers of the dollars that the US central bank has poured into the market since the 2008 financial crisis. It would be naïve to expect them to be affected by the European Commission’s fines. Equally, it would be naïve to expect the Commission to go beyond fines to structural measures. The ship of the European Union is not big enough or strong enough to withstand the waves that are rising more and more every day. They cannot afford to open such a front with Trump. Therefore, the regulation of digital platforms will remain an area where a bunch of lawyers, EU bureaucrats, competition economists and academics like us are kicking the ball around, with no impact on material life.

4. What about Turkey?

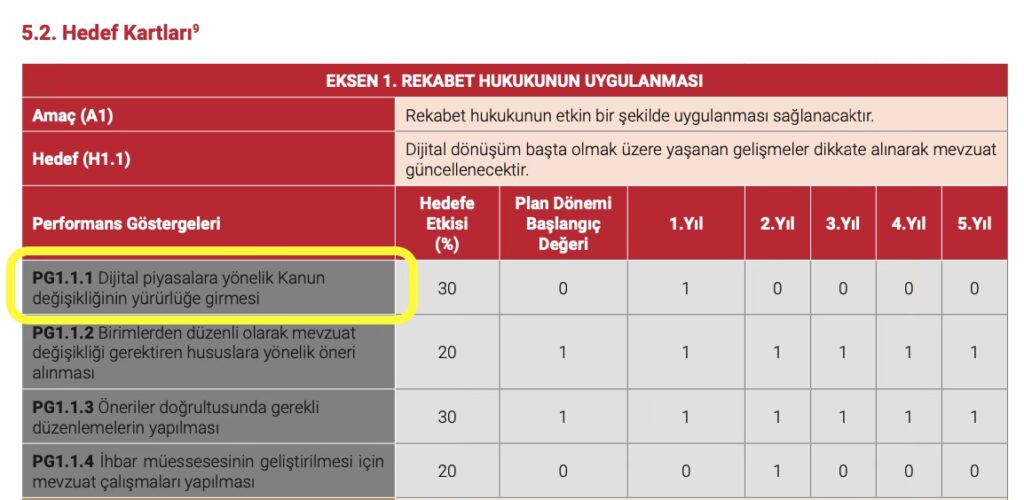

Last August, the Competition Authority published its strategic plan for the 2024-2028 period. The plan focuses on introducing DMA-like amendments to the Competition Act to regulate digital platforms. I welcome this as a perfectly understandable effort. Digital platforms are arguably the most important area where a competition authority should have something to say today. (You probably don’t want to read another line on the importance of digital platforms in the economy and the alarming competition problems there, do you?)

The first target in the Strategic Plan is the enactment of a law amendment on digital markets.

However, I do not know whether the Turkish Grand National Assembly will share the priorities of the Competition Authority and put this draft law on its agenda. There are actually many convincing reasons for it to be put on the agenda. Or it is more accurate to say “it was so before Trump was elected”.

Let’s first take a look at the arguments in favor. I think the Competition Authority officials have clearly informed the country’s administration about the regulatory framework that will emerge with a future amendment to the law. As you know, these amendments will lead to digital platforms operating under ex-ante regulation. In other words, companies will be subject to additional obligations not because of their behavior, but because of the size of variables such as the number of users they have and the sales revenue they generate. Thanks to the detailed data set that the Competition Authority has created through various sector studies, it should have a preliminary study on which platforms will be above and which will be below the planned regulatory threshold. If the impact on the market and companies of the additional obligations to be imposed on those above the thresholds were well explained to the executives (there was once a regulatory impact analysis, but what happened to it?), I think they would agree to give such a power to the administration.

The most important obstacle to the draft law is that no one other than the Competition Authority has publicly voiced the need for such a regulation in Turkey. As you know, since we are a digitalized society, what is written on X and the reactions given have a great impact on the governance of the country. Now, the second obstacle is the effort to keep in touch with the Trump administration.

In fact, most of the platforms that would be affected by a possible DMA-type regulation in Turkey are not of American origin. Those that are certainly have a much higher impact on society, but in terms of turnover and visibility, Chinese, Turkish, Kazakh, Qatari and German-owned platforms are ahead. And they are likely to be more influenced by the Americans.

In conclusion, as I wrote above, competition policy is a tool that can be applied very selectively. Therefore, who uses it and for what purpose is as important as the content of the rules. However, the likelihood that the hawkish implementation of a policy with sanctions that go as far as breaking up companies will be met with the brake of “Stop for God’s sake, it’s already a mess” has increased a little more after the elections. Because it is already a mess.