The EU Commission’s approach to online marketplace bans, as outlined in the revised VBER, may not be accepted by all competition authorities. The Turkish Competition Authority (TCA) is one of these authorities. The TCA viewed suppliers’ attempts to prevent their dealers from selling to online marketplaces as resale price maintenance (RPM) and imposed penalties on them. In our article, we analysed the TCA’s decisions in this regard.

1. Challenges and Reactions: How Traditional Distribution Networks Adapt to the Rise of Online Marketplaces

The rapid expansion of online marketplaces has dramatically altered the consumer products landscape, impacting sectors from sports apparel and consumer electronics to kitchen appliances and cosmetics. Suppliers, traditionally reliant on authorised dealer networks for product visibility in physical retail settings, face challenges from online competition threatening the profitability of these channels. In Türkiye, as in many Western European countries,[i] these products have traditionally been distributed through selective distribution systems.

In response to online competition, suppliers have adopted strategies such as monitoring online pricing, issuing warnings and penalising dealers who disrupt traditional retail pricing by selling on online marketplaces. The EU has observed similar trends, with the rise of e-commerce prompting adaptations in selective distribution systems. European Commission’s sector inquiry found that 56% of manufacturers use selective distribution agreements for some products, though these represent a smaller fraction of all agreements. With e-commerce’s growth, 19% of manufacturers introduced selective distribution systems where none existed, and 2% expanded their systems to cover new product categories. Moreover, 67% of those using selective distribution revised their agreements with new criteria to adapt to the changing retail environment.[ii]

Drawing on communication evidence uncovered by the Turkish Competition Authority (TCA), one can explore dealers’ and suppliers’ immediate reactions and adjustments to the challenges posed by online marketplaces. This highlights how dealers and suppliers resist adapting to digital challenges that disrupt established distribution channels and influence product sales and pricing.

A WhatsApp message from 2017 reveals a managing director from a household appliance manufacturer inquiring about vacuum cleaners advertised online at lower prices than their listed rates, indicating concerns over online pricing undermining traditional sales. He asked one of his subordinates to purchase vacuum cleaners he had seen online in order to identify the authorised distributor who had sold them to the seller on the online marketplace.[iii] Earlier, the same individual cautioned distributors against bulk sales or offering significant discounts to wholesalers who might resell online, emphasising the importance of maintaining suggested retail prices.[iv]

In another instance, a heating and cooling systems company manager mentioned monitoring online prices[v] and taking action against dealers who set prices too low in another e-mail in 2018.[vi] This company also actively purchased discounted products from online marketplaces to identify the authorised distributor responsible for selling these items to the listing owner on the online marketplace.[vii]

In 2018, a finance manager for a sports shoe brand consulted legal counsel about a memo to distributors aiming to restrict their sales on online marketplaces.[viii] That year, a kitchen appliance manufacturer also communicated with its distributors about the challenges and competitive pressures introduced by the launch of Amazon Türkiye, advising caution in selling on such platforms.[ix]

During the sector’s evolution, suppliers and their authorised dealers in the consumer goods market initially resisted adapting their sales practices as a network. Their immediate response was to ban online marketplaces as a sales channel and closely monitor dealers to prevent cheating so that they maintain desired price levels. Suppliers were particularly concerned about the appearance of their products on online platforms, fearing that it would undermine the credibility of their list prices and result in a loss of control over product distribution in the future.

2. Türkiye’s approach to online marketplace bans and RPM

The TCA revised its Vertical Guidelines accompanying the Block Exemption Communique[x] in March 2018 to address better how the internet has changed how goods are distributed. By aligning with the European legislation, Türkiye showed its commitment to adopting broader European standards, recognising the internet’s role in expanding market access and increasing choices for consumers and suppliers alike. A fundamental principle in these guidelines ensures that all resellers can sell products online. These sales are considered passive sales, stemming from consumers’ initiative to visit or contact the seller. The guidelines also support the adoption of quality standards for online sales and the establishment of physical sales points within selective distribution networks. The Vertical Guidelines allow suppliers to require sales through online marketplaces that meet specific standards as long as they do not unduly restrict online sales or price competition. [xi]

The TCA considers resale price maintenance (RPM) as a hardcore restriction that harms both intra-brand and inter-brand competition, which is not possible to benefit from an individual exemption rather than a case-by-case assessment:

“Considering that price competition is the main factor that ensures efficiency in the markets and thus increases economic welfare, it is clear that the elimination of price competition will have a significant negative impact on consumer welfare, and it will be equally difficult to demonstrate a positive effect that can offset this negative effect.” [xii]

In addition, as the current case law of the TCA considers RPM practices as an “infringement by object”, it does not consider it possible to subject them to an individual exemption assessment.[xiii]

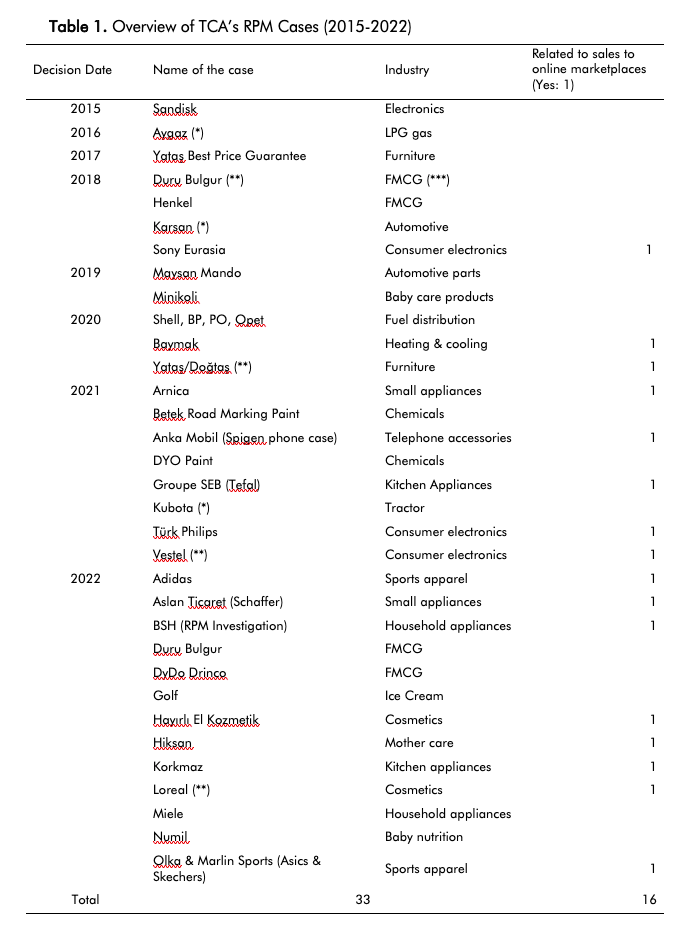

Our analysis from 2015 to 2022 shows that the TCA conducted 33 investigations into RPM cases. Of these, 16 found that the scrutinised undertakings were involved in RPM by enforcing online marketplace bans. Notably, between 2015 and 2018, no cases related to online marketplace bans were concluded. However, there has been a gradual increase in such cases, with a total of 8 concluded by 2022 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Surge In Turkish RPM Cases Related to Online Marketplace Bans

Source: Compiled by the author from the reasoned decisions of the TCA.

Table 1. Overview of TCA’s RPM Cases (2015-2022)

Notes:

* Upon judgement of the Administrative Court

** Preliminary investigation

*** FMCG: Fast Moving Consumer Goods

Source: Compiled by the author from the reasoned decisions of the TCA.

In all 16 RPM cases related to online marketplace bans, the supplier opted for a selective distribution system. Again, all the suppliers were manufacturers or importers of non-fast-moving consumer goods, such as consumer electronics, household appliances, shoes, sportswear, and cosmetics (see Table 1). These findings support our claim that many branded consumer goods suppliers take advantage of the protection against unauthorised re-sellers offered by the selective distribution system to prevent their products from going through online marketplaces.

Starting from 2018, there was a noticeable uptick in RPM enforcement, leading to more frequent penalties. In contrast, no infringements were identified between 2015 and 2017. By 2021, three investigations culminated in violations with administrative fines imposed, and two cases were settled.[xiv] This approach was adopted in an additional nine investigations in 2022. The ratio of being penalised as a result of these investigations has also gradually increased (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. RPM Investigation Conclusions

Source: Compiled by the author from the reasoned decisions of the TCA.

3. Analysis of TCA’s policy

We witnessed two different types of infringement evaluated together: The online marketplace sales bans and the RPM. We can better understand why these two are mentioned together by looking at the development process of online marketplaces. Online marketplaces sometimes use branded products as “loss leaders” and run campaigns to attract consumer attention, which could damage an important feature of branded products in the eyes of the consumer: consistent pricing regardless of the seller. Similarly, the appearance of low-priced products from dealers offering high discounts in online marketplaces created unrest among suppliers and dealers who wished to avoid price competition within the network. Traditional distribution systems aimed to combat online marketplaces by utilising legal protection through selective distribution, preventing the sale of their products there for the reasons mentioned above. This was an attempt to stifle a powerful, unpredictable, and insubordinate new sales channel.

The argument for banning sales to unauthorised sellers in products that require a perception of luxury during the sales experience and in technical products that require after-sales service, does have some merit in terms of increasing consumer welfare. However, in most cases before the TCA, it was concluded that the aim of the businesses was not to protect brand perception and service quality but rather to enforce minimum resale prices. This was determined by evaluating the correspondence within the distribution networks, as we illustrated in Section 1.

In certain cases, it was mentioned that the simultaneous presence of RPM and the prohibition of sales to online marketplaces was part of the supplier’s overall strategy.[xv] Yet, in other instances, it was noted that the sales prohibition was an extension of RPM to enhance its effectiveness and should be viewed as a single violation.[xvi] Even in cases where this distinction wasn’t explicitly made,[xvii] the TCA still imposed penalties for a single violation by stating that the offending businesses had violated Article 4 of the Law, which prohibits agreements that restrict competition.

Nevertheless, the TCA believes online marketplaces benefit consumers by increasing economic efficiency and promoting dynamic competition. The TCA did not want to restrict this rapidly growing channel, so it viewed the ban on selling through online marketplaces as a restriction of passive sales. This ensured any block or individual exemption would not cover it. In cases where evidence of RPM was found, the TCA imposed penalties. If no evidence of RPM was found, the investigations were concluded after obtaining a commitment to remove the blanket online marketplace sales bans.

When evaluating the legality of bans on online marketplace sales, the TCA does not consider them eligible for exemption even if the market share is below 30%. The TCA examines whether these bans comply with the requirements of the Vertical Block Exemption Communiqué.[xviii] The TCA views such sales bans as hindering passive sales, considered a hardcore restriction, and therefore excludes the agreement from the scope of the block exemption under Article 4 c of the Communiqué. This article states that the authorised dealer cannot be prohibited from making active or passive sales to end users in the selective distribution system.[xix]

TCA assesses the eligibility of the vertical restraint for an individual exemption after evaluating for the block exemption regulation. Even if the online marketplace sales ban is not implemented along with the RPM,[xx] the TCA rules that the individual exemption conditions are not met for such blanket bans. In the individual exemption assessment, it is recognised that the reasons put forward by the undertaking to justify the prohibition, such as the risk of free-riding and the protection of the brand image, are important. However, it is emphasised that there are less restrictive measures to achieve the aforementioned objectives. Furthermore, the benefits of the Internet to consumers were mentioned, and it was stated that the restriction was unlikely to be beneficial for the consumer.[xxi]

There have been instances where TCA approved revisions to suppliers’ sales policies in online marketplaces. In two cases, suppliers of household appliances allowed their dealers to create accounts on these platforms and sell their products as long as they adhered to the specific brand guidelines provided by the supplier.[xxii]

Conclusion

Platforms have redefined how all products, especially consumer products, are sold. When they entered the market, they offered surprising discounts on attractive products to attract consumers. The disarray created by the platforms disturbed the established distribution networks of suppliers. Distribution networks tried to fight back by prohibiting dealers from selling on online marketplaces. However, since such an action also meant preventing them from going below the list prices set by the supplier, it was considered as RPM and penalised by the TCA. Nevertheless, numerous decisions on this issue shed light on the principles under which suppliers can regulate their dealers’ ability to operate on sales platforms.

List of Turkish Competition Board Decisions

TCA Decision No. 11-39/838-262 of 23.06.2011, Anadolu Elektronik.

TCA Decision No. 15-28/318-96 of 7.7.2015, Sandisk.

TCA Decision No. 16-39/659-295 of 16.11.2016, Aygaz.

TCA Decision No. 17-30/487-211 of 27.9.2017, Yataş Best Price Guarantee.

TCA Decision No. 18-05/74-40 of 15.2.2018, Jotun Exemption.

TCA Decision No. 18-07/112-59 of 8.3.2018, Duru Bulgur Preliminary Investigation.

TCA Decision No. 18-10/196-92 of 5.4.2018, Karsan.

TCA Decision No. 18-33/556-274 of 19.9.2018, Henkel.

TCA Decision No. 18-44/703-345 of 22.11.2018, Sony Eurasia.

TCA Decision No. 19-11/129-56 of 7.3.2019, Minikoli.

TCA Decision No. 19-22/353-159 of 20.6.2019, Maysan Mando.

TCA Decision No. 20-08/83-50 of 6.2.2020, Yataş, Doğtaş.

TCA Decision No 21-11/154-63 of 04.3.2021, Groupe SEB.

TCA Decision No. 20-14/192-98 of 12.3.2020, Shell, BP, PO, Opet.

TCA Decision No 20-16/232-113 of 26.3.2020, Baymak.

TCA Decision No. 21-22/266-116 of 15.4.2021, Anka Mobil.

TCA Decision No. 21-22/267-117 of 15.4.2021, DYO Paint.

TCA Decision No. 21-37/524-258 of 5.8.2021, Türk Philips.

TCA Decision No. 21-42/611-298 of 9.9.2021, Solgar Exemption.

TCA Decision No. 21-42/617-303 of 9.9.2021, Vestel Preliminary Investigation.

TCA Decision No 21-46/671-335 of 30.9.2021, Arnica.

TCA Decision No. 21-46/673-337 of 30.9.2021, Kubota.

TCA Decision No. 21-61/857-421 of 16.12.2021, Betek Road Marking Paint.

TCA Decision No 21-61/859-423 of 16.12.2021, BSH Individual Exemption.

TCA Decision No 22-09/130-50 of 17.2.2022, Duru Bulgur.

TCA Decision No 22-18/300-133 of 21.4.2022, Adidas.

TCA Decision No 22-29/483-192 of 30.6.2022, Numil.

TCA Decision No 22-29/488-197 of 30.6.2022, Olka & Marlin Spor.

TCA Decision No 22-32/508-205 of 7.7.2022, DyDo Drinco.

TCA Decision No 22-33/523-210 of 21.7.2022, Hayırlı El Kozmetik.

TCA Decision No 22-41/579-239 of 8.9.2022, BSH RPM Investigation.

TCA Decision No 22-41/580-240 of 8.9.2022, Arcelik Investigation.

TCA Decision No 22-48/696-294 of 20.10.2022, Loreal.

TCA Decision No 22-51/753-312 of 10.11.2022, Miele.

TCA Decision No 22-51/754-313 of 10.11.2022, Korkmaz.

TCA Decision No 22-52/771-317 of 23.11.2022, Natura Gıda (Golf).

TCA Decision No 22-54/834-344 of 8.12.2022, Aslan Ticaret.

TCA Decision No 22-56/882-365 of 22.12.2022, Hiksan.

TCA Decision No 23-36/684-236 of 03.08.2023, BSH revised commitments.

[i] EU Commission. (2017). Staff Working Document accompanying the document Report from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament: Final report on the E-commerce Sector Inquiry (Report No. SWD/2017/0154 final). Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52017SC0154, para 227.

[ii] See EU Commission (2017, chap. 3.4.3) for detailed findings on suppliers’ reactions against online marketplaces.

[iii] TCA Decision No 21-46/671-335 of 30.9.2021, Arnica, para. 59

[iv] TCA Decision Arnica, para.52

[v] TCA Decision No 20-16/232-113 of 26.3.2020, Baymak, para. 30

[vi] TCA Decision Baymak para.50

[vii] TCA Decision Baymak para.84

[viii] TCA Decision No 22-29/488-197 of 30.6.2022, Olka & Marlin Sport, para. 54

[ix] TCA Decision No 21-11/154-63 of 04.3.2021, Groupe SEB, para. 108

[x] TCA Block Exemption Communiqué No 2002/2 on Vertical Agreements.

[xi] TCA Vertical Guidelines, para. 28.

[xii] TCA Decision Group SEB, para. 297, 298.

[xiii] TCA Decision Anadolu Elektronik (2011). This decision has set a precedent and is cited in almost all of the RPM investigations’ reasoned decisions in Table 1.

[xiv] The settlement mechanism offers companies an opportunity to obtain a reduction in fines by refraining from defence until the case’s conclusion.

[xv] TCA Decisions Arnica para. 73 and Group SEB.

[xvi] TCA Decision Olka & Marlin Sports para. 168 and TCA Decision No 22-54/834-344 of 8.12.2022, Aslan Ticaret para. 53.

[xvii] TCA Decision Baymak can be given as an example.

[xviii] See for example TCA Decision BSH Exemption. In some cases, such as Olka Marlin Sport, market share assessment was not done at all.

[xix] In Olka Marlin Sport, Article 4 b of the Communique was used to exclude from the cover of the block exemption (para. 157) due to the lack of a selective distribution system.

[xx] See TCA Decision No. 18-05/74-40 of 15.2.2018, Jotun Exemption, TCA Decisions BSH Exemption and Solgar Exemption.

[xxi] See TCA Decision Hayırlı El Kozmetik para. 69.

[xxii] TCA Decisions Arcelik Investigation and BSH revised commitments.